A Poem-Collage Project

Poem by Sarah Glaz with Collage by Mark Sanders

The poem-collage pair appears in the Bridges 2023 online art gallery; https://gallery.bridgesmathart.org/exhibitions/2023-bridges-conference/sarah-glaz-mark-sanders

|

|

History, Mathematics, Poem, Collage

Eratosthenes

(276 BCE - 194 BCE) was born in Cyrene, a Greek city located in

what is present-days Libya, and was educated at Plato's Academy

in Athens. As a promising young scholar, he was invited by

Ptolemy III to Alexandria to serve as tutor for his son and heir

to the throne.

Alexandria was a Greek city situated in Egypt at the mouth of

the Nile. It was founded in 331 BCE by Alexander the Great, and

prospered after his death under the Ptolemaic rule. The

Ptolemies made Alexandria into the center of Hellenistic

intellectual life. They built the Museum (seat of the Muses), a

forerunner of the modern university, and its library, known as

The Great Library of Alexandria, which housed the largest

collections of papyrus scrolls in the ancient world. At the

height of its glory, The Great Library of Alexandria contained

about half a million papyrus scrolls, some of which were housed

in a nearby annex, the Serapeum -- the temple of the god

Serapis. The Museum was an institute of research and pursuit of

learning, attracting a large number of scholars from the

furthest reaches of the Hellenistic world. In particular,

science and mathematics flourished at the Museum like in very

few other periods of time in history. During its several hundred

years of existence, the Museum produced, in addition to Euclid

who founded the Museum's school of mathematics, other

distinguished scholars whose work determined the course of

future mathematics: Archimedes, Eratosthenes, Apollonius,

Claudius Ptolemy, Diophantus, and Hypatia were all educated or

otherwise affiliated with the Museum.

Eratosthenes

became the chief librarian of The Great Library of Alexandria in

his early thirties. He served in this position for over 40

years. Eratosthenes was a polymath, producing work in geography,

philosophy, history, astronomy, mathematics and literary

criticism. He was also a poet.

Although, admired by many of his contemporaries for the

breadth of his knowledge, his detractors nicknamed him Beta,

the second letter of the Greek alphabet, implying that although

he was knowledgeable and creative in many areas, he was first

rate in none.

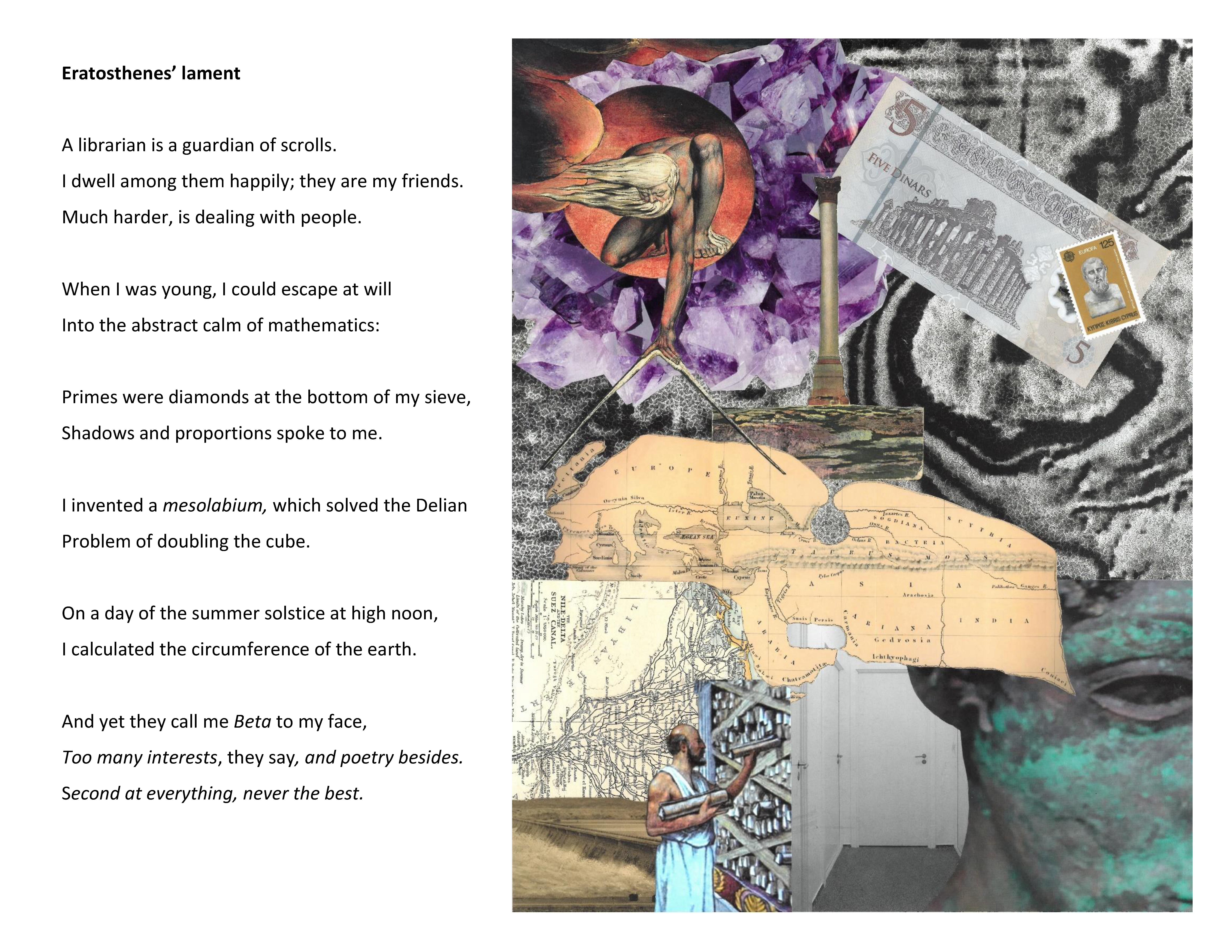

Certainly not Beta in the area of mathematics, among Eratosthenes' mathematical accomplishments we count the first attempt to put geographical studies on a sound mathematical basis, including the drawing of the most accurate map available at that time of "the habitable world" appearing in the center of the collage. He also discovered a technique for finding prime numbers less than a given number, called The Sieve of Eratosthenes, which is used to these days. Mentioned in the third stanza of the poem, it appears symbolically as the purple diamonds in the top left corner of the collage. In addition, he was the first to devise a method for calculating the circumference of the earth that yielded reasonably accurate results. Eratosthenes noted how shadows fell in different geographical locations at the same time of day, and used the resulting angles and other geometric considerations to estimate the earth's circumference. This accomplishment, mentioned in the fifth stanza of the poem, is reflected in the collage's imagery through the shadow-casting pole and the compass yielding figure at top left. The pole is an image of Pompey's Pillar, the last remaining ancient monument in Alexandria, standing adjacent to the ruins of the Serapeum. The figure looming above it, is from William Blake's design "Ancient of Days," which is itself a reference to the Book of Proverbs viii. 27 "when he set a compass upon the face of the earth." Together, the images of compass and pillar evoke the permissible tools of ancient Greek geometry, the straight-edge and compass. Eratosthenes himself considered his greatest achievement to be the construction of a mesolabium, a mechanical device that calculated the "mean proportionals" necessary for the determination of the side of a cube that duplicates the volume of a given cube. The duplication of the cube, mentioned in the fourth stanza of the poem, does not appear explicitly in the collage. It is hinted at by the cube-like space between the doors in the right bottom corner. The compass and pillar mentioned above are a reminder that although this was a geometric result of some significance, Eratosthenes' duplication of the cube, was not obtained through a pure straight-edge and compass construction, but rather by the use of a more crass mechanical device. For more details, see Mark's Dissecting Eratosthenes' Lament.

According to some historical accounts, in old age

Eratosthenes lost his sight, and unwilling to live when he could

no longer read, he committed suicide by refusing to eat.

Many thanks to Claudine

Burns Smith for the technical expertise with which he

formatted the poem-collage pair to Bridges Art Exhibit

specifications.